Guest post by Rebecca Wilson, Skyward

The importance of having an efficient, scalable process for drone flight ops can’t be overstated: It will save you time and money, enable excellent customer service, empower your crew to do their best work, and allow you to scale up as your business grows. This article shares best practices for planning and executing drone flights anywhere in the world, but the Q&As at the end are specific to Part 107, the federal rules that regulate commercial drone operations in the United States. We created a 60-page guide to Part 107, which you can download here (it’s free).

Remember: The best ops planning processes prioritize efficiency and make safety and compliance part of the workflow.

When we conduct commercial flights at Skyward, we follow a five-phase process.

1. Understand why your customer needs aerial data

This is all about engaging with your customer or internal colleague, asking the right questions, and communicating well. Take the time to understand your customer’s expectations at the outset in order to save time and money and provide the best service—even if it means declining the job. Your customer is anyone requesting your UAV services, including a colleague within your company.

Ask these questions:

- What is the final product that you expect?

- When do you expect it?

- What is your budget?

Then, analyze the customer’s requirements. Are you able to meet them?

- Can you undertake the job without violating airspace regulations?

- Using a validated drone airspace map, check to see whether the job is within controlled or restricted airspace where you may need special permission to fly.

- Do you have the aircraft and qualified personnel needed to perform the job?

- Do you have the permits, licenses, and insurance needed to perform the job?

- Do you and your crew have the time? Are your schedules full?

- Is the budget reasonable? Or would you lose money if you were to undertake it?

- Is there a more cost-effective way of achieving the same result? For example, if a construction site already has cranes, it’s possible that attaching cameras and sensors to the cranes would be cheaper and safer than removing the crew from the construction site in order to conduct drone flights.

If you have the time, availability, crew, aircraft, insurance, permission, and expertise to undertake the job, you’re ready to start planning.

2. Plan the UAS flight operation

More than any other, this step will ensure that your crew operates as efficiently as possible.

Evaluate airspace

Using a validated drone airspace map, take a look at the location of the job. During the job engagement phase, you determined the type of airspace in which you’ll need to fly to

complete the job.

For example, if the job is in a certain class of airspace, you may need to coordinate with air traffic control or apply for a regulatory waiver. If the job requires that you fly over your crew, you’ll need to plan for and conduct a safety briefing beforehand and arrange for security to keep non-participants out of the area. If you need to fly directly over non-participants, such as on an active construction site, you’ll need to apply for a waiver, which could significantly affect your scheduling.

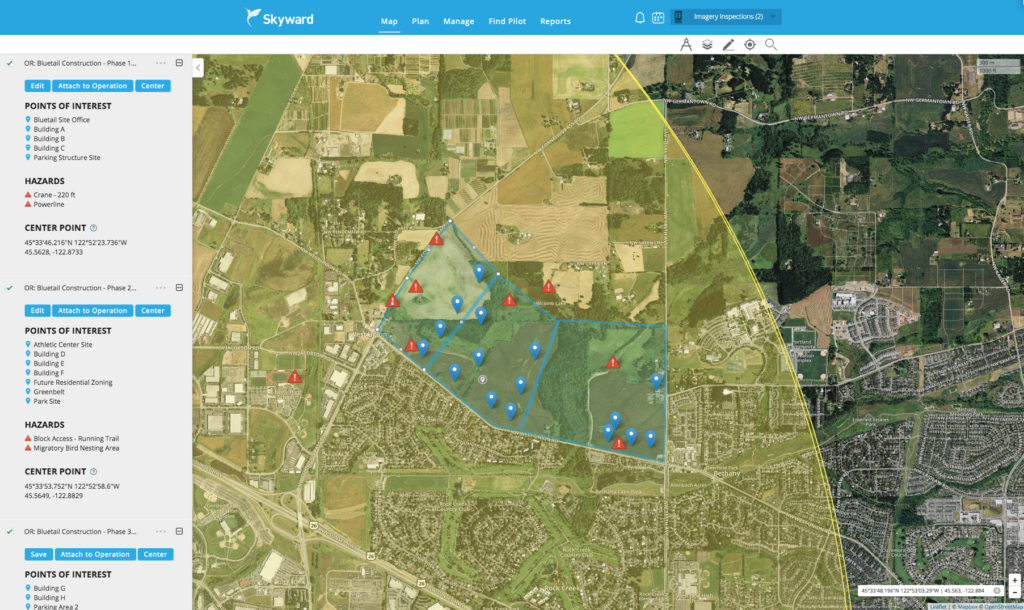

In this example, Skyward mapped a tract of land for a property developer outside of Hillsboro, Oregon. As you can see from this view of the Skyward Airspace Map, the land is located entirely within controlled (yellow) airspace. So we contacted the Hillsboro Airport to coordinate. It took us 35 days to obtain the necessary flight permission.

Create a flight area

Depending on the scope of the flight job, your flight area may be very large (eg, a wildlife survey) or highly constrained (eg, inspecting a cellular tower). Regardless, the area should encompass your crew’s rally point and takeoff and landing areas. In the Hillsboro example above, our pilot-in-command decided that the tract of land was large enough to warrant three separate-but-adjacent flight areas (the blue polygons).

Mark points of interest and hazards

Your crew needs to know exactly what’s expected of them, including rally points, potential takeoff areas, where they need to fly, when, and the type of data they need to recover. Mark points of interest and record these details so they can see everything in advance and avoid guesswork once they’re in the field.

Also, show your crew potential hazard areas, such as power lines, roads, and high-traffic pedestrian areas that may need to be blocked off, or obstructions which may block the line of sight or be collision hazards.

Here is a completed flight plan in Skyward.

Coordinate with your field crew and schedule the job

Share the flight plan with your flight crew and make sure that everything makes sense to them. Check your crew’s availability, and remember to factor in extra time if you need to obtain special permission from a regulator or landowner.

Other scheduling considerations:

- Make sure your UAVs and batteries are available.

- Make sure that your available pilot-in-command has been trained to fly the UAV scheduled for the job.

- Do you have enough batteries for the planned flight duration?

- Do you need to coordinate traffic control?

- Does your client require that you have an escort or supervision to enter the job site?

- Depending on the time of year and weather in your area, you may need to add a buffer to your schedule to account for weather-related delays.

Confirm with your customer

Send your customer screenshots of your flight plan and confirm that all the details have been accounted for.

3. Focus on safety, efficiency, and professionalism

On the day of the flight, check your validated drone airspace map again. Temporary flight restrictions can happen at any time—for example, if there is a forest fire or public safety emergency, or if a head of state comes to town.

There may be a way to work with regulators even in the event of a temporary flight restriction, but don’t settle for verbal approval—insist on getting it in writing. Also, take a look at the weather. If it’s raining, snowing, foggy, or very cold, you may have to reschedule for another day.

Once on-site:

- Certain job sites, such as construction sites, can change quickly, so take a few minutes to observe your surroundings.

- Check the weather, including temperature and windspeed.

- Are there non-participants in the area? If so, they will likely need to be briefed and kept away from certain areas.

- Are there structures that are higher than you are allowed to fly?

- Begin your preflight checklist.

Aviation Runs on Checklists

For more than a century, aviation has run on checklists, including preflight, in-flight, postflight, and emergency checklists. Checklists remove variables and lower risks by ensuring that complex processes and procedures are carried out the same way every time.

At Skyward, we’ve created our own 130-page General Operating Manual and Operational Checklists (download a preview here) in collaboration with aviators, UAV experts, regulators, and insurance providers.

4. Close out the flight job

As soon as the crew finishes the job, they should carefully inspect the data before leaving the site. If there’s an error, it’s much easier to fly again than it is to pack up, go back to the office, discover a mistake, and drive back to the job site.

At the end of the day, pilots should log their flights. In general, flight logging involves two types of data, which should be reflected in your system of record:

- what the human beings did and

- what the aircraft did.

All aviators log flights in order to maintain pilot credentials, track training requirements, and be prepared for regulatory audits—airspace authorities routinely review pilot logbooks.

Crew training programs and maintenance requirements need the support of logged flight data. You’ll also need to know how long an aircraft has been flown in order to schedule routine maintenance.

For all pilots, flight hours are the major benchmark of professionalism and credibility and they can only be tracked by logging flights.

In terms of your business, UAVs represent a major investment. But they only provide return value if they’re being used. Logging flights will show you whether you’re maximizing your investment.

Flight logging is essential for:

- Understanding the totality of your operations

- Keeping a record of adverse incidents, such as collisions

- Tracking pilot hours

- Maintaining training schedules

- Promoting a pilot to pilot-in-command

5. Deliver the aerial data

For your customers, this is the most important part. UAVs have an enormous capacity to quickly and efficiently capture data, but raw data is rarely enough to meet the customer’s

requirement. Raw data must be turned into knowledge to help the customer meet a business need.

This may involve mapping or video editing software. Depending on the type of service you provide, you may also be expected to interpret raw data so your customer can easily make use of it.

If you’re a major corporation, you probably already have the systems in place to handle that type of logistical challenge. If you’re a small business, you may need to invest in image processing or data analysis systems in order to use the information you gather.

Questions about Commercial Drone Operations Planning

Q: 333 Exemptions required a monthly flight report, even if you haven’t logged any flights. Does Part 107 have reporting requirements?

Part 107 does not require monthly reports unless you have a separate waiver that requires it. The FAA only requires incident reports if there are injuries or property damage exceeding $500 (other than to the UAV involved).

Q: How does Part 107 affect flight operations over people? As a law enforcement agency, a 60-90 day lead time could prohibit us from accident/crime scene investigation. Part 107 does make it difficult to fly over nonparticipants, even with a waiver.

Options include:

1) Operate under Part 107 but make sure not to directly fly over unprotected non-participants. Part 107 does not specify a minimum distance.

2) Apply for an Exemption that allows you to fly over non-participants. For safety reasons, we recommend option 1.

Q: The waiver takes 60-90 days to process. Is this project-based or can you obtain a blanket waiver?

We have seen waivers take as little as 30 days and as many as 90. Remember, there is not a “blanket waiver” under Part 107. The FAA is developing a Certificate of Waiver (CoW) that we hope will be much faster than the Civil COA process. The waiver may be generalized to a type of operation or specific to a location and time depending on the complexity of the operation and the impact it has on airspace safety.

Q: Does anything in Part 107 affect how a local government agency would obtain approval for drone use?

Local governments can choose to operate under Part 107 or request a Public Certificate of Waiver or Authorization for certain operations.

Q: Does Part 107 have the same property owner permission requirements as the 333 Exemption? What are the “borders” of private airspace? When are you over someone’s airspace instead of in it. For example, regular manned aircraft do not ask for permission to fly over properties.

Part 107 does not require permission to overfly private property but it may still be an excellent practice, depending on the situation—use good judgment. The FAA refers to the National Telecommunications and Information Administration Voluntary Best Practices for UAS Privacy,23 as well as local trespassing ordinances. Part 107 does specify that you cannot directly overfly any person not participating in your operation, or endanger people or property on the ground, but it doesn’t specify a minimum distance.

Q: For aerial photography what is required to fly over a property in order to photograph a different property. For example to photograph my house, I fly over my neighbor’s yard. Is there any ruling on who owns the airspace over a person’s land? What permission is needed from landowners?

Part 107 does not require operators to receive permission from landowners before flying over their property. Landowners don’t own the airspace over their property. However, in certain cases, it’s a great idea to ask for permission anyway. Following the law is one thing, being a professional is another. If you’re flying over a large vacant lot, there’s probably no need to contact the landowner. But if you’re flying over your neighbor’s house, we recommend asking permission.

Q: Will UAV operators be required to maintain communication with air traffic control during flight operations?

Not unless you are operating under a certificate of waiver that requires air traffic control communication. This may happen if you wanted to operate inside controlled airspace.

Q: Is there any regulatory process underway to allow commercial drone flights within the Washington, DC Flight Restricted Zone?

We have not seen any indications of this. Technically, the NOTAM implementing the FRZ states that flight is not allowed without permission. But it does not specify how permission is to be obtained.

Q: Is it true that under Part 107, we don’t operate under a COA any longer?

If you choose to operate under Part 107 rather than your 333 Exemption, you will no longer be subject to a the Blanket COA (which means no more monthly reports!). However, certificates of waiver will still be required to operate in certain types of airspace.

Q: What is the Part 107 regulation regarding first-person viewing (FPV), and will that change?

Part 107 does not prohibit first-person viewing, but FPV doesn’t meet the requirements for maintaining visual line-of-sight with the aircraft. Part 107 requires the remote pilot-in-command to be able to see the aircraft at all times without aids other than glasses or contact lenses. This would seem to not allow the remote-PIC to use any FPV devices which block normal vision. The FAA has stated that they don’t have enough data to validate the use of FPV as an acceptable method of meeting the requirement to detect-and-avoid other traffic. It’s possible that in the future enough data may become available to allow the FAA to validate the use of FPV. The visual line-of-sight requirement is waiverable, but Part 107 seems to not allow the use FPV as a method of providing equivalent level of safety (ELOS) during a beyond visual line-of-sight operation (BVLOS).

Q: Has there been any legal definition of “people directly involved in the operation” as stated in Part 107?

Part 107 does not contain the phrase “people directly involved in the operation.” 14 CFR 107.39 prohibits operation over a human being unless that person is “directly participating in the operation of the small unmanned aircraft.” This means crew, not subjects, bystanders, or any other people. Without offering a legal opinion, a crew may be as small as one person (remote-PIC) or have many members (remote-PIC, remote-operator under remote-PIC supervision, visual observer, sensor operator, aircraft handler, operator of ground equipment necessary for the operation, etc). The intent is that anyone who may be directly overflown is aware of the risks and is under the control or coordinating authority of the remote-PIC. Flights directly over non-participants are not allowed, but flying over participants is allowed.

Q: We have seen FAA communications that speak about a minimum safe distance of 25 feet; however, the online training for Part 107 makes it sound like you need to get everyone completely out of the way. For example, would a group photo be allowed as long as it doesn’t fly directly overhead?

Under Part 107, flying over human beings not directly involved in the operation of the UAV (that is, the crew) requires a waiver. A condition of the waiver may be that the flight is conducted at a closed-set or controlled-access area (a film shoot or a construction site, for example) and that the people being overflown have all received safety briefings, are aware that the flight is happening, and understand the risks. It’s important to note that these are provisions of the waiver, not Part 107 itself, which does not allow flying over human beings not directly involved in the operation of the UAV. This is a little different from a section 333 Exemption which grants permission to operate over people on a closed set or controlled access area.

Q: I regularly fly over privately owned agriculture fields. Will crews working in the fields need to be removed before flights? Will I need to get special approval to be conducting flights over people?

Unless you can either ensure that the people working in the field will not be overflown by the UAV or those people are under safe cover during the flight, they should be removed from the field prior to the flight. Careful preflight planning and coordination may make it possible to ensure that you don’t overfly anyone.

Q: I work at a construction company, and we sometimes need to fly a drone over a job site or quarry during working hours when many different types of workers are onsite. We will obviously need to waive the rule that prohibits flight over unsheltered persons. Does the fact that construction or quarry workers are required to wear personal protective equipment such as safety glasses and hard hats mean that they are protected?

Part 107 does not seem to consider personal protective equipment (PPE) such as hardhats or safety glasses as being equivalent to “safe cover.” That said, you should include that information along with the fact that the operation will be conducted at controlled-access construction sites, and that you will notify all the workers before the flight in your request for a waiver. This will demonstrate to the FAA that you can operate with an equivalent level of safety and not endanger anyone on the ground.

Q: I use the DJI app to log flights. Should I get a paper logbook as well?

If you’re running a business, we don’t recommend using paper logbooks. They require too much legwork, they’re unsearchable, and they don’t provide reports or business insights. Of course, we recommend logging flight ops in Skyward in order to understand the totality of your flight ops.

Q: Does the flight log need to be more like my log in a Cessna 162 or can I use the DJI app as my flight log?

The FAA does not specify the form of the flight log required. If you have even two aircraft or pilots, we highly recommend having one, external flight log as your business’s system of record. That is one of the core features of the Skyward platform.

Q: Does closed-set filming under Part 107 require a waiver and motion picture manual just as Section 333 did?

Yes, you will need a waiver to fly directly over people. The reference to a specific MPTOM is not in Part 107 but you will need to submit as part of your waiver request your operations and safety procedures. This may be a motion picture and television operating manual (MPTOM) or a controlled access ops manual.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle The latest drone news

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle The latest drone news