The FAA’s remote ID cohort hopes to launch at last one remote ID service supplier by sometime next year, according to documents viewed by Avionics. (Airbus)

The Federal Aviation Administration is planning to have remote ID service for drones — a foundational component of integrating unmanned aircraft into the national airspace — up and running by sometime next year, according to documents viewed by Avionics International.

Earlier this month, the FAA chose a cohort of eight companies to develop technology requirements for its implementation of remote ID, working in parallel with the agency’s policymaking process. A critical goal for that cohort, according to documents obtained by Avionics, is to launch remote ID services through at least one UAS service supplier (USS) by 2021.

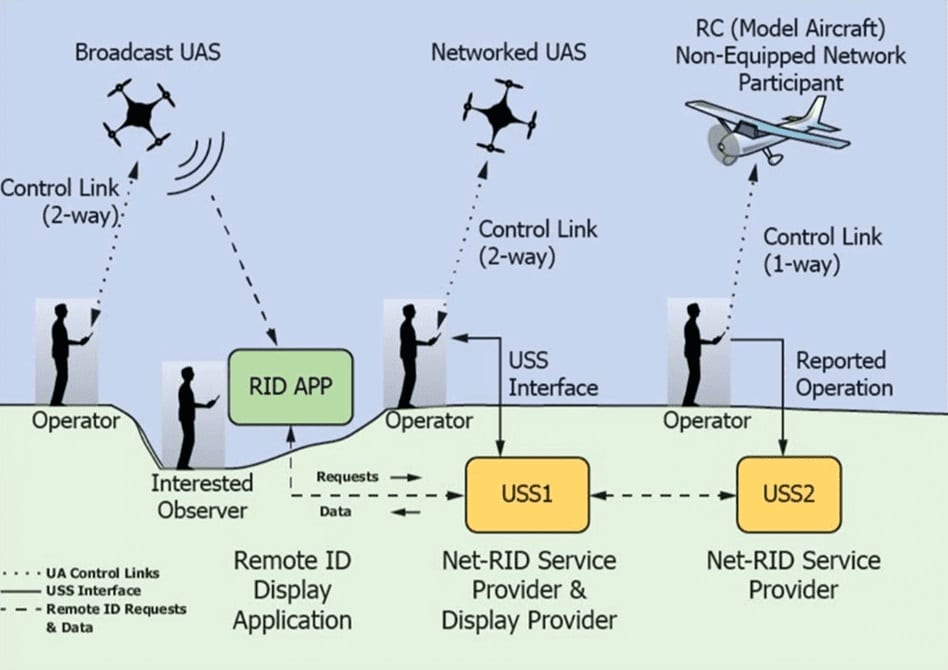

Through the remote ID system described in the agency’s proposed remote ID rule, released in December 29, drone operators will be required to transmit via broadcast and network their location, their drone’s location, velocity and identifying data to a centralized system, which a variety of remote ID USSs share and retrieve information from in near-real-time. That publication received more than 53,000 comments from the public, including UAS service providers, hobbyists, law enforcement agencies and many other stakeholders concerned about the cost of compliance, privacy implications, timeline for implementation and much more.

The following companies were selected by the FAA to form the remote ID cohort:

- Airbus, which will participate via AirbusUTM, a component of Airbus Acubed

- AirMap

- Amazon, which operates PrimeAir

- Intel

- OneSky, spun off from AGI (recently raised a Series A)

- Skyward, owned by Verizon

- T-Mobile

- Wing, owned by Google

With the inclusion of Intel, Skyward and T-Mobile, the remote ID cohort is noticeably network-heavy. Many dissenting voices, including drone manufacturing giant DJI, have argued that broadcast alone is sufficient to enable remote ID; the FAA’s choice of three telecom providers and its exclusion of DJI from this cohort indicates proceeding with a primarily network-based solution, perhaps mandating broadcast as well or including it as a backup option.

“This initial group will support the FAA in developing technology requirements for other companies to develop applications needed for Remote ID,” an FAA press release reads. “The applications will provide drone identification and location information to safety and security authorities while in flight.”

An image included in the FAA’s December 2019 remote ID proposed rule. (FAA)

Documents obtained by Avionics provide some insight into how the cohort is building the RIDEx system, including the how the technology is taking shape and what controversial issues are being tackled:

- How will the FAA access remote ID information? Original plans suggested the creation of a “baseline stream” of data automatically flowing to FAA servers, but according to documents viewed by Avionics, the cohort has since abandoned that idea — at least for initial rollout — in favor of a Discovery and Synchronization Service (DSS) defined in the remote ID standard published by ASTM International. Rather than a nationwide unmanned traffic management system, it appears the FAA, along with other qualified agencies and public-facing apps, would query flight information through the DSS from participating USSs based on a grid system.

- How often will the remote ID information update? The cohort is currently requiring a transmission rate of “at least once per minute,” a frequency rate not capable of providing real-time deconfliction services, for example, but that creates less burden on cellular networks throughout the country.

- Should the operator or ground controller’s location be included in remote ID? So far, this appears to still be an element of the data captured by remote ID. This may create a compliance challenge and/or safety concerns, particularly if that information is made public.

The FAA acknowledges that enabling the public to understand what is flying above them is a key component of the system, according to viewed documents, but what counts as fulfilling that goal is still being defined.

Reached for comment on this matter, Wing referred to the ASTM standard, which includes what type of drone is flying (quad/fixed-wing/VTOL), drone ID, type of license, speed, and altitude as information to be made public.

“The UTM system will be a different system than we see today with ATC/ADS-B because this is a different type of aviation, but it should include the safety tools and relevant information that people can use (the public, law enforcement etc.) to be able to react to drones,” a representative for Wing told Avionics.

Considering the planned one-minute refresh rate, the FAA appears to be choosing a low-capability remote ID system that is perhaps more feasible in the short-term, rather than a more robust functionality that might run into significant coverage and bandwidth problems. It is worth noting that the draft rule released by the agency proposes at minimum “a transmission rate of at least 1 message per second,” stating that this is achievable by existing systems.

Compared to a once-per-second transmission rate, that requirement also significantly reduces the amount of historical data available on drone flights. Through broadcast, observers — including law enforcement organizations — would be able to track drones in near-real-time, but it will likely be difficult using one one ping per minute to track the path of flights that have already taken place using network-based applications. Again referring to the draft rule released in December, the FAA defined one of the purposes of remote ID as “to provide greater situational awareness” of drones operating within the national airspace; an objective which is less fulfilled by a slower transmission rate.

An FAA representative declined to provide comment for this article, stating the agency is currently in the rulemaking process.

It is worth noting the lack of a law enforcement organization in the remote ID cohort, despite the project’s goal of assisting security authorities with tracking and identifying drones. If remote ID is to allow for greater integration of drones into the national airspace, it must fit seamlessly into how police conduct day-to-day operations.

FAA administrator Stephen Dickson publicly pushed for the agency to release its final rule by the end of this year — an already-aggressive goal for a complex rulemaking process during an election year that now may not be possible due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

“The technology is being developed simultaneously with the proposed Remote ID rule,” according to the FAA press release. “Application requirements [to become remote ID service suppliers] will be announced when the final rule is published.”

Stakeholders across the drone industry are anxiously awaiting a final remote ID rule and technology architecture — some, to make investment decisions related to enabling infrastructure; and others, to survive until a larger market for drone services is made possible.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle The latest drone news

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle The latest drone news