The Great Sand Dunes National Park in southern Colorado announced the completion of a research project earlier this week that used drones to collect data within the park.

This is a big news, primarily because drones are generally banned from all national parks.

[Skip down for some analysis of drones in national parks and related legal questions, or continue reading to learn more about the Great Sand Dunes project.]

The research project used drones to create accurate geospatial maps of the sand dunes, and provide researchers with high quality data sets about the dunes.

Image Source

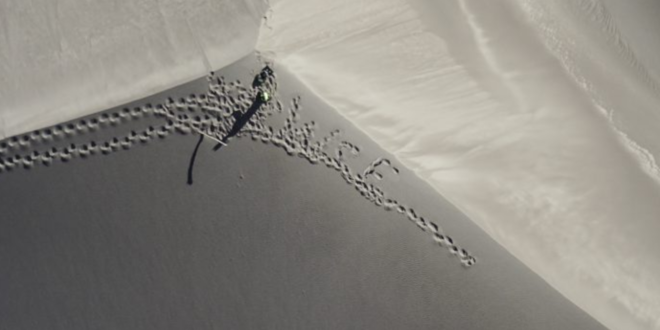

Star Dune seen from 400 feet above its surface. The image was compiled using high-resolution photos taken from a Black Swift Technologies drone on Oct. 19, 2016.

About the Great Sand Dunes Project

Monitoring the changing heights of the dunes, and how they shift over time, is part of the work required of the staff at Great Sand Dunes National Park. Historically they have done this work on foot, since vehicles aren’t allowed to drive on the dunes. But with the highest dune reaching to 755 feet tall, and the vast area of land to be covered in the park, doing regular full ground surveys is almost impossible.

Drones provide a possible solution, and this project’s goal was to do an initial test run.

Image Source

The Great Sand Dunes flyover happened on a single day, October 19, 2016. The drone took high-resolution images of 1 square mile of the park centered around the Star Dune (pictured above), which is the tallest dune in North America, at 750 feet tall.

The project was a collaboration between the NPS, Black Swift Technologies, and Wohnrade Civil Engineers, with permission from the FAA. Wohnrade Civil Engineers was the FAA-licensed service provider for the flight, using a SwiftTrainer fixed-wing drone that had been developed by Black Swift Technologies.

“The park monitors the dunes to see how much they shift. How high are the dunes? Is it higher in elevation than last year? It’s generally for in-house research…The milestone project will give research staff at the park meaningful data for monitoring change detection within the dune field, and to quantify, visualize and interpret resources it is charged with protecting.”

– Mary Wohnrade, President of Wohnrade Civil Engineers

Said Steve Sorenson, aviation manager for the intermontane region of the National Parks Service:

“The early flights were more of a test than anything else, and any future flights will likely result in us gaining the appropriate NPS approvals to launch from within.”

The final deliverables from the project were:

- High-resolution georeferenced orthomosic image;

- Topographic mapping at a 1-foot contour interval;

- 3D model of the 1-square mile area of interest;

- Georeferenced point cloud.

Some History about Commercial Drone Pilots, the FAA, and the National Park Service

Back in June of 2014, the National Park Service banned the use of drones in all of its 401 parks. This ban came on a wave of one-off bans that had been made at various national parks throughout the U.S. (You can find the ban itself on the NPS website.)

In 2013, the year before the national ban was announced, drone pilot and videographer Raphael Pirker got into a public skirmish with officials at Grand Canyon National Park, a fight that ended up in court and thrust the entire debate about commercial drones into the spotlight.

Pirker’s story is a fascinating piece of the evolution of the FAA’s attitude about drones, in part because he was the first person to have been fined by the FAA for piloting a drone.

At the time, Pirker was told he had violated an FAA regulation created for commercial airplanes. According to a Wired article:

“The $10,000 levy [against Pirker] invokes the same code section that governs the conduct of actual airline-passenger pilots, charging modeler Raphael Pirker with illegally operating a drone for commercial purposes and flying it ‘in a careless or reckless manner so as to endanger the life or property of another.’”

But Pirker was eventually acquitted, which was a huge victory for commercial drone pilots. The presiding judge on his case publicly declared not only that Pirker wasn’t in violation of the FAA regulation in question, but went even further, saying that “there are no laws against flying a drone commercially.”

This ruling made big problems for the FAA. They were now faced with the reality that there were no regulations on the books to help them regulate the burgeoning industry of commercial drone pilots, which, up until this point, they had simply declared illegal. Now commercial drone operations in fact appeared legal, and legislation needed to be created to deal with that fact.

Fast forward from June of 2014, when NPS issued their ban, to June of 2016 when the FAA issued Part 107, and you can see how the FAA’s regulatory ability has evolved and grown more nuanced over time.

So Is It Illegal to Fly a Drone in a National Park?

We will admit, the law still seems to be grey. Although the NPS has clearly issued a ban on drone flights, it’s unclear whether they actually have the right to do so.

Technically, the FAA has jurisdiction over all airspace, including the airspace over National Park Services land. However, NPS can certainly ban people launching, landing, or operating a drone on their land (this distinction comes into play in a recent Orlando ordinance requiring drone pilots to be permitted, and we can only imagine we’re going to be hearing a lot more about it).

The loophole this wording leaves open is for pilots to fly drones over NPS land while standing outside NPS demarcations—but then you almost certainly will run into BVLS (Beyond Visual Line of Sight) scenarios, which are clearly not allowed by Part 107.

Although you could argue the point and weigh the technicalities even further, ultimately we feel like this is a situation where pilots should honor the wishes of the NPS.

There are a host of reasons why the NPS doesn’t want drones flying over federally protected lands.

Some of these reasons have to do with avoiding harm to the animals that live there, and others have to do with generally preventing a scenario where the skies are so full of drones that one of the main reasons for having protected areas (that is, to provide quiet, serene spaces removed from the advances of technology) becomes lost.

We’ll admit that this latter scenario seems unlikely right now, but we can understand why the NPS might want to be proactive in eliminating that possibility. And as bullish as we are about drones, we’re OK with the idea that there are some spaces that still remain untouched.

Zacc Dukowitz

Zacc Dukowitz is the Director of Marketing for UAV Coach. A writer with professional experience in education technology and digital marketing, Zacc is passionate about reporting on the drone industry at a time when UAVs can help us live better lives. Zacc also holds the rank of nidan in Aikido, a Japanese martial art, and is a widely published fiction writer. Zacc has an MFA from the University of Florida and a BA from St. John’s College. Follow @zaccdukowitz or check out zaccdukowitz.com to read his work.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle The latest drone news

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle The latest drone news