The Russian invasion of Ukraine has seen the extensive use of Ukrainian and Russian unmanned aerial vehicle footage as propaganda for each side, spurring much discussion on both the possible offensive uses of aerial drones, and means of defending against drones.

Fortem Technologies’ DroneHunter is a drone defense system that has already intercepted Russian drones in Ukraine, earning the title of “Shahed Hunter” for the system’s role in intercepting Iranian-made Shahed suicide drones used by Russia during its campaign targeting Ukrainian infrastructure during the autumn and winter of 2022.

Overt Defense had the opportunity to speak with Jon Gruen, chief executive officer of Fortem, on the DroneHunter’s use in Ukraine, and how the lessons learned from its combat experience have shaped its continuing development

To start things off, can you introduce yourself and Fortem Technologies?

I’m Jon Gruen, the CEO of Fortem Technologies. I served in the U.S. Navy, and then worked at Lockheed Martin for 11 years, working in business development and strategy. And then I started working with commercial venture capital-backed companies that wanted to get into the aerospace and defense market with their dual use technologies, using them to work with the government, other companies and the investor side.

And that led to me coming to Fortem three and a half years ago, where we’ve been working to grow the offerings and our market over that time and really create what is the premier counter drone system in the world, particularly from a low collateral effects point of view, but also from an air awareness point of view.

The F700, or the DroneHunter as we call it, is the only drone that effectively goes and catches other drones in a low collateral effects manner. It is based on our original core radar technology. Our co-founder, chief technology officer Adam Robertson, was a radar specialist. He worked on radars for many, many years and developed the core technology that he was able to spin off from another company and strike out on his own. It’s a low size, weight and power, active electronically scanned phased array radar.

When you reduce the size, weight and power, that starts creating a form factor that’s small enough to be used in a lot of different ways compared to what was traditional about 10 years ago. And the small radar, we call it the R20, was the size of a pencil case, if people remember what that used to look like.

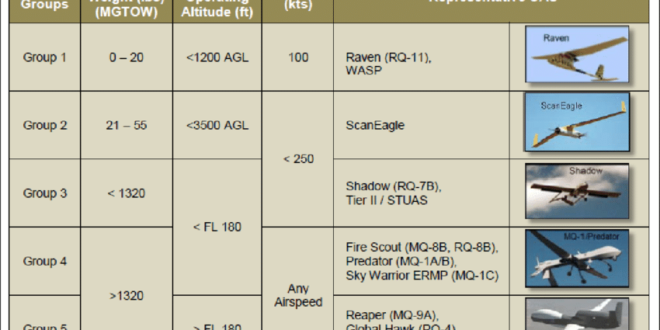

We were advertising that, and working with a number of different partners to provide that radar on different platforms and then different systems in the market. And along came the US government, DARPA in particular, and they said, “We really like that radar. What would happen if we put that on a Group One or Group Two size drone, particularly a VTOL, to see what it would be capable of?”

That kicked off an effort that we’ve been working on for over six years now, developing the F700. The current F700 is a VTOL style low end Group Two drone under US specifications, so bordering on 50 pounds total weight, that has the ability to autonomously go and catch Group One and Group Two drones and grab them with two net options.

The original version, which is the version we use in most configurations today, is driven by the desire to have a low collateral effect. When you’re grabbing the target with the net, they’re either able to be towed off to a defined point where you bring it down to the ground. What we’ve developed over time for larger, heavier drones, is a net that actually releases a drogue parachute that reduces the forward velocity of the drone and drops it out of the sky under that parachute, so it comes down in a controlled manner.

Both versions are considered low collateral effect. They keep the drone intact as it’s coming out of the sky and that enables a number of different opportunities, both obviously from not having collateral damage, but also now being able to do forensics on the drone, exploit the drone, all those different elements that you would want.

The F700 platform has been used as far back as the 2020 Olympic Games, and we were at the Qatar World Cup last year in all the different stadiums and mobile sites that were used to provide security for all the venues. The system was going through Department of Defense testing as well at the time. But when the Ukrainian war kicked off, we saw that we had immediate applicability to go intercept drones, particularly the Group 1 and Group 2 intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) drones that the Russians were using to surveil the battlefield and find Ukrainians.

And so we gave two systems to a unit in Ukraine. They took it and started working with it, developing tactics and procedures to maximize its effect and really started being able to grab those smaller drones immediately. We’ve had over a year of grabbing Group 1 and Group 2 ISR drones in the Ukrainian conflict. But what became apparent was that there were obviously emerging threats coming from the Russian side. The most well-known at this point is that you had Shahed-131 and 136 suicide drones.

There certainly are others, they already had the Orlan-10s, which is a fixed-wing ISR drone used for spotting and targeting. That targeting resulted in Lancets (Russian loitering munition) being used as the effector by the Russians to come in.

The Russians have adopted new technologies, they’ve adopted their tactics, and we’ve been right alongside the Ukrainians to counter those new technologies on the battlefield. We modified the F700 to be able to go get the Orlan-10s when they’re in their ISR orbits. We modified the F700 to be able to go get Shaheds, which are a very different, very large 200 kilogram drone that goes a very long distance.

And that required shooting a different configuration of the nets and parachutes and various other hardware modifications to our payloads. We’ve been addressing all those challenges, all those new threats on the battlefield including the electromagnetic spectrum. This is unlike what the Department of Defense has seen in the War on Terror, where we’ve had air superiority, we’ve had electromagnetic superiority on the battlefield.

And in this case, with Ukraine and Russia being in such close proximity and both using electronic warfare systems, it’s created an entirely new environment on the battlefield. So both sides are conducting a lot of jamming, a lot of energy is in the environment, and how do you operate systems and electronic systems in that environment?

We’ve worked through those challenges to keep the system operational and effective. And so there’s been a whole range of developments from hardware, through software, through incorporation of new more advanced subsystems to enable the drones.

You’ve mentioned the use of the DroneHunter system at the 2020 Olympics and then the 2022 Qatar World Cup. Has the DroneHunter operationally intercepted any drones during the events or in service with other clients before Ukraine?

The DroneHunter was tested in those environments, but thankfully it was not needed operationally. So it was fully operational in those environments, but it didn’t need to catch anything.

There wasn’t that level of threat involved in those two events. There were certainly other tests with other customers. We have a number of different government customers around the world that have operationally intercepted drones, but I’m not at liberty to name those.

Can you disclose whether or not the intercepts in question happened before or after the DroneHunter was sent to Ukraine and started intercepting Russian drones?

Active captures probably were all during the Ukrainian timeframe, that’s when the proliferation of the threat really started. Ukraine kicked off a new dynamic of warfare, and that has proliferated quickly to other areas of the world. Both the proliferation of the threat has taken off since the start of Ukraine, and the recognition that you need a counter drone system like ours has been parallel with that. We’ve seen a major uptick in our deployments and partnerships about the time the invasion kicked off, and that was when a lot more activity started happening globally.

On the DroneHunter’s use in Ukraine, what drove your decision to go public with your system’s use in Ukraine and its interceptions?

Well, that was actually a Ukrainian decision. They wanted to advertise, so to speak, or make known the fact that they had such a high end capability, an effective capability, to really start to deter Russian action, and that’s proven to be true.

We always defer to our customers on whether they would like to release information and it’s through them. And so they’ve chosen to view it as a deterrent to let people know that our system is protecting their critical infrastructure.

Who’s procuring the DroneHunter systems for Ukraine? Fortem press materials mention the US government supplying it as aid, but we’ve also seen the Ukrainian government suggesting they privately acquired some, and then there are also some private charities or fundraisers by Ukrainians that also have resulted in Drone Hunters being bought and delivered.

I think a very interesting dynamic that’s coming out of this conflict is the ability to, for lack of a better word, crowdsource donations to provide technical capabilities to someone like the Ukrainians.

We started out donating a couple systems free of charge. And when they were successful, the Ukrainians went out and crowdsourced donations through the United24 fund, which has provided a large number of different drone capabilities to the Ukrainians during this conflict. That increased our numbers in the country. Meanwhile, the Ukrainians used the time to find their own internal budgets for the next series of buys, and they were concurrently going out and asking partner governments around the world to provide different types of assistance. And so the next step in that evolution is governments supporting Ukraine using their funds to acquire and donate systems.

So it’s been a mix of all three. It really has been kind of that evolution where those donations were the quickest way to get technology, and as governments work through their processes, which is the nature of a government. That has been the evolution of those funding sources throughout this conflict.

With multiple means for the Ukrainians to acquire the DroneHunter system, what has training the system operators and maintainers been like?

We have some incredibly dedicated professionals who are out there in Ukraine training Ukrainian system operators. They’ve been there rotating constantly since early on in the conflict. They’ve established a great rapport with the operators in Ukraine. That’s been great as the number of trained personnel on the Ukrainian side has increased dramatically over the last year plus, and it is also a great venue for us to get user feedback and make modifications to the system to make it more effective in the reality of their operating environment. So we’ve had a full commitment and a full presence in Ukraine since early on in the conflict.

How long does it take to train an operator to use the DroneHunter?

For basic use, it takes 3 hours. For full training for support, it takes 3 days.

What has the consumption of the interceptor nets and drones been like?

The drones themselves are remarkably robust and we’ve had very, very few losses. The vast majority of them are fully operational the entire time, they are easily maintained by the Ukrainians themselves. They’re actively using them daily, so we have an aggressive demand for replacement nets as they continue to use them on the front lines and around critical infrastructure all throughout Ukraine.

Has there been a ramp up in production of both nets and drones in response to this demand, or is it just the nets?

It’s been both. We continuously have steady orders for Ukraine through those various funding mechanisms, routine orders for the F700 itself, and then continuous orders for replacement parts.

What is the most up-to-date interception count that you know of?

We get our information from our ministerial level customers in Ukraine, and of the small Group 1, Group 2 ISR drones, which are critical to negate in order to remove the targeting capability of the Russians, we’re very, very much in the high, high multiple numbers of 10s routinely. It’s not exact, but we have intercepted very high numbers of those.

When it comes to the Shahed–136, obviously it’s got an explosive warhead. How does the DroneHunter system handle this so the warhead doesn’t go off unintentionally?

Interestingly, the Ukrainians certainly have a higher risk tolerance for explosive ordnance, and particularly if it’s not coming down on top of critical infrastructure. That’s a way of saying that the way it comes down with the net around it, with the drogue chute, it is coming down at a very controlled rate, and typically in non-populated areas. So if it were to explode, there usually is very little around to affect. In the ideal case, the fusing system on the Shaheds is not activated at all. And we’re starting to see a lot more ineffective Shaheds currently, as our technology and our capabilities start to outpace what the Russians are able to develop.

Has the system been subject to Russian electromagnetic warfare at this point?

Yes, a lot, and we’ve evolved the system to be highly effective in that environment.

Whenever it comes to the issue of drone defense, you see one prevailing line of argument that the interceptors or the interception system is always much more expensive than it is to fire off another wave of Shaheds or whatever drone of the week is being mentioned. How do you respond to that?

Well, that’s why the Department of Defense recognized early that a system like ours is so critical for a modern battlefield because you have two elements going.

One is the decreasing effectiveness of radiofrequency energy-based systems as the drone threats evolve and become less dependent on signals for navigation, or less affected by energy themselves. So you’re seeing adversary drones becoming RF hardened to the point where energy is not affecting them very much. And so you need to go get those drones out of the air in a kinetic manner.

And so that leads into what you’re referencing, the fully kinetic explosive-type solutions, which at this point are very high-end missile and rocket systems. And those have a limitation of A – being expensive, and then B – being low volume. It is cost prohibitive, but just physically being able to deploy large systems like that is very logistics intensive, and so they are not readily available.

A system like ours sits in that sweet spot, being able to be deployed widely and at much, much lower cost and having extremely high effectiveness against that range of threats.

You’ve mentioned acquiring feedback from the DroneHunter’s operation in Ukraine. What are the main types of feedback that you’ve received that you can share?

Obviously one is that electromagnetic environment. It’s not just knowing that there’s jamming out there, but understanding the types of jamming, the power levels, the frequency levels, all of that. So there’s that immediate operational feedback on what the operational environment really is, and what’s happening out there.

There’s basic usability type functions like how to transport it, how to recharge batteries, how to more efficiently change out net heads and just basic things that operators find out from heavy usage of the system.

And then you get into the most recent tactics the Russians are using, which gives us a heads up to start developing any other capabilities or product improvements that we need to match those threats. So it’s across the board on all levels, but it’s vitally important and really has driven our development almost holistically as a company over the last 14 to 15 months.

What improvements are currently being made to the DroneHunter system based on the user feedback you have received?

We have made improvements to operate in those heavily jammed, electromagnetically intense environments, being able to continue operating with the high 90% probability of kill that we have, being able to affect bigger and faster drones as they start coming into the battlefield.

Add to that the combination of better nets, better materials, better artificial intelligence. As we see more and more threat profiles, our artificial intelligence learns and learns how to maximize its attack vectors on those threats, so it’s a constant learning on all elements of the system. So again hardware, software with the AI, and more robust subsystems that can operate in those very intense environments. Our radar technology is being improved for better range and capabilities as well.

So what’s next for the DroneHunter system, aside from those specific refinements?

We’re partnered with the Ukrainians and dedicated to help them win this conflict, which they will. And part of that is maximizing the F700’s performance in the current battlefield.

It’s also making it as useful as possible to the customers. We call it multi-mission, so different payloads, either for different types of threats or for a number of different missions. If an F700 is not being used actively in a counter-UAS posture at the moment, it can do other things. It’s a very robust low-end Group Two VTOL platform. Things that we’re exploring with customers are demining capabilities, the detection of mines, potentially even mitigation of some mines, the ability to do basic surveillance, and logistics missions.

So it’s being asked to be used in a number of different ways to have maximum effect for the customers. The radars that we deploy as part of the air awareness package, the detection package, we’re having discussion with on further uses as they are being used widely around many parts of Ukraine and critical infrastructure in Ukraine. And the future, we already are in discussions of how the future of Ukraine will look and that we’re committed to a long-term partnership with Ukraine as it goes through its rebuilding phase. And our core technologies are there to be a part of that.

Ukraine wants to build back as one of the most digitally enhanced, digitally modern societies on the planet, with things like drone delivery and autonomous vehicles, unmanned taxis and such. The future of advanced air mobility, and everything that encompasses, that is all enabled by the sensors and software that we have. And so as we are working on those kinds of pilot programs in various parts of the world, bringing that capability to the rebuilding phase of Ukraine in particular is something we’re very excited about in the coming years.

As a company that’s been donating the DroneHunter system from early on, what’s your take on the current debate on how quickly should allies of Ukraine be providing more ammunition, more advanced weapons systems, and more training to Ukraine’s military?

Obviously every government has real concerns about what it’s willing as a government, as a society, to provide to the conflict, either side of the conflict, in our case the Ukrainian side. But what I’ll say is that the Ukrainians have been very, very good at adopting new technologies and new capabilities to this conflict. And so I think the bigger issue or topic with allied governments should not be “how do we do more of the same?”, it’s “how do we provide these newer capabilities to Ukraine that have been developed in their operational environment, and have been adopted by the Ukrainians and used highly effectively?”

And that may not be a standard rocket system that’s been around for 20 years with potential issues because it wasn’t developed for this type of conflict. We’ve been working very closely with our Ukrainian partners and the United States government to develop systems that don’t cross red lines and don’t create collateral effects. And those types of requirements where it really is ideal to have a system built to operate in that environment effectively, but also not pose any issue to governments procuring them for Ukraine, because they don’t cross any red line thresholds.

There are a number of other systems that have been developed out there. Ours, I think, is at the forefront of that, and has the opportunity to be deployed at scale to really neutralize a large portion of the Russian threat. And so I think that the conversation needs to change to not be “do we continue aid or reduce aid”. It is definitely “continue aid”, but we need to continue supplying the right capabilities, and in this case it’s the newer capabilities to the Ukrainians to resolve the conflict in an amenable way to all sides.

Speaking of scaling, with both the increased demand from Ukraine and the increased use of the core technologies in other fields, are there any plans to scale Fortem’s research and production capabilities to meet projected future demand?

Absolutely. We’re already well down that path. We have a range of sensors that we offer, visual sensors as well as the radars. We have many partners in the radiofrequency space, our command and control software that controls the sensors and the drones and the effectors has matured greatly, and we’re continuing to do that.

All of it is based on artificial intelligence, so the software that is in the sensors themselves, the software that’s working out of the command and control center, the software that’s controlling the effectors and the drones, all of that is continuously progressing and learning, and so that’s being rolled out in different increments to the customers.

And then on the effector side we’re looking at different versions of the DroneHunter, with different sizes, different payloads, and different ways to defend against the upcoming drone threats. We’re actively working on a number of mitigation effectors for countering swarming drones. So we have a very robust development plan for all segments of our system.

What’s your take on the Department of Defense’s new Replicator drone development program?

We are involved with the program, and we are supportive of further developments along these lines.

Thank you to

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle The latest drone news

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle The latest drone news