News and Commentary. Recreational drones – once the darling of drone headlines and drone manufacturers alike – may be taking a backseat to the commercial drone industry.

News and Commentary. Recreational drones – once the darling of drone headlines and drone manufacturers alike – may be taking a backseat to the commercial drone industry.

When Paul Misener, vice president for global innovation policy and communications for Amazon, gave a keynote address at the InterDrone 2016 conference in Las Vegas yesterday he spoke about the company’s much publicized efforts at drone delivery – Amazon Prime Air. The delivery service has been moving steadily forward in development in testing over the last two years, mostly outside of the US due to regulatory issues. Now the company says that Prime Air is well along in its development – and they are offering their plan to integrate drones into the NAS (National Air Space) and make the whole thing possible.

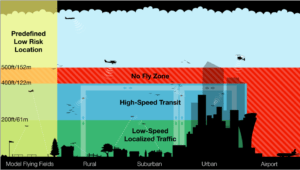

Amazon’s been selling their concept of a “federated airspace” for some time now – Amazon’s drone delivery guru Gur Kimchi delivered a rousing sales pitch for the plan at the AUVSI show last spring. But this time around, there seemed to be a slight emphasis on one point – that the plan is designed to integrate commercial drones, relegating recreational drones to pre-defined low-risk areas. Which may not, in fact, include the drone operator’s own backyard.

The speech got some reaction from recreational operators on Twitter after attendees at the conference pointed it out. But the reaction has not been significant – perhaps because Amazon’s plan is only a proposal, and not an government sponsored template, or perhaps because most recreational drone operators have been more interested in developing their skills and enjoying their aircraft than in following the increasingly complex regulatory environment.

They may need to start paying attention. The recently released Part 107 Small UAS Rule has been widely viewed as a commercial drone regulation – but as John Goglia writing for Forbes pointed out a few weeks ago, the rule actually blurs the distinction between recreational drone operators and commercial drone operators. The registration rules for hobby fliers and commercial fliers are different. The licensing, however, may be the same: the FAA now says that recreational fliers must belong to a community-based flight organization like the AMA – and fly within its framework – or take the Part 107 test.

On the surface, this would seem to make sense. As the commercial drone technology evolves, many commercial applications can be performed using a “consumer” style drone. Some manufacturers, in fact, are making the switch to more profitable commercial aircraft- 3DR announced last year that they would be shifting their focus from the recreational Solo to a commercial product. DJI has also beefed up its offerings to include more professional drones; the Phantom 4 is something of a cross-over, offering features appropriate to both recreational fliers and many commercial operators. Requiring all operators of the same drone to demonstrate the same skills is not unreasonable, and it is certainly to the benefit of all stakeholders in the drone industry to limit the number of embarrassing “rogue drone” incidents. But designating only small areas as legal for recreational drone use goes further than other plans, and could make it just too difficult for responsible operators to fly.

The Amazon plan is troubling on a number of fronts – it demonstrates that even industry leaders, deep in the weeds of trying to figure out drone integration, don’t quite know what to do with recreational flyers. It shows that as the economic and human benefits of the drone industry become more and more apparent, big business is pushing for a say in making the laws – Amazon is now one of the top lobbyists in Washington. And it’s another alarm bell for recreational drone operators who have long been on the defensive, fighting close regulation on a state and local level, that federal regulations may be changing around them.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle The latest drone news

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle The latest drone news