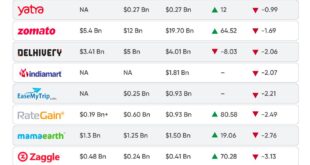

The House Judiciary Committee’s Antitrust Subcommittee this week released the 400-page findings of its 16-month investigation into the “state of competition in the digital economy.”

WASHINGTON, DC – JULY 29: Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos testifies via video conference during the House … [+]

The predetermined results cited a “clear and compelling need” to “strengthen antitrust enforcement and consider a range of forceful options, including structural separations and prohibitions on anticompetitive conduct” against the likes of Facebook, Amazon, Apple and Google.

The use of the word “force” is telling, given the voluntary nature of markets and consumer choice.

Antitrust regulation is a prominent illustration of how unhinged and concentrated hyper-regulatory power, not just spending authority, enables and encourages massive compulsory transfers of wealth by government. Every generation or so we go through the motions of “modernizing” antitrust only to invent complex new rationales reviving it for every major new frontier sector because, this time, we really mean it, it’s really different and government needs to step in.

Market actors today find themselves accused by so-called trustbusters of being too big, reducing consumer welfare, raising rivals’ costs, and—in the latest iteration—of doing other bad things like interfering with free speech.

In a release accompanying the new report, House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jerrold Nader (D-New York) proclaimed, “As they exist today, Apple

It would have been more appropriate for Nadler to have acknowledged, “As it exists today, the Federal government and state co-conspirators possess significant market power over large swaths of our economy.” The sane, good-government “consumer welfare standard” is no match for that fervor, so the antitrust subcommittee produced this “slate of recommendations” instead:

- Structural separations to prohibit platforms from operating in lines of business that depend on or interoperate with the platform;

- Prohibiting platforms from engaging in self-preferencing;

- Requiring platforms to make … services compatible with competing networks to allow for interoperability and data portability;

- Mandating that platforms provide due process before taking action against market participants;

- Establishing a standard to proscribe strategic acquisitions that reduce competition;

- Improvements to the Clayton Act, the Sherman Act, and the Federal Trade Commission Act, to bring these laws into line with the challenges of the digital economy;

- Eliminating anticompetitive forced arbitration clauses;

- Strengthening the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice;

- And promoting greater transparency and democratization of the antitrust agencies.

Republicans agree with many of these and with antitrust intervention generally, as made clear by the antitrust subcommittee minority response issued by Rep. Ken Buck (R-Colorado). A contemporaneous Trump tweet on his displeasure with the tech giants’ content moderation cap-yelled, “REPEAL SECTION 230!!!”

Section 230 is the slice of the 1996 Communications Decency Act that shields websites from liability for user-generated content, and it now weighs heavily in the antitrust revival. Monkeying with Sec. 230 would actually benefit the giants from one perspective, since they will inevitably have a hand in the modifications, and since a rival of their scale could never emerge without its protections. What’s for sure is that gullible Republicans will not control the administrative apparatus affirming the “neutral” political speech they demand. Yet there’s plenty more antitrust advocacy to be found in the GOP ranks, which, sadly, reveals they are advocates of the administrative state.

Antitrust is something of the original sin of the administrative state, though there were major classes of government intervention preceding it such as national banking, tariffs, public subsidies and the infamous Interstate Commerce Commission. Republicans’ continued antitrust boosterism means they prefer yielding to the administrative state rather than insisting upon adherence to the constitutional one; that renders their concern about over-regulation elsewhere suspect as well. As a category of unpredictable government intervention openly hostile to property rights, antitrust’s very presence is distortionary, perhaps more so than other forms of regulation.

Over a hundred years after the smokestack era that spawned antitrust, companies competing in code are being treated as essential facilities by both left and right. We now find demands made for the most extreme “remedy” of all — corporate breakup — which has not proven beneficial to consumers in the past. Apparently we can only satisfy all parties if all search results appear first.

All Search Results Must Appear First

It is the federal government and its coercive antitrust intervention that perform the misdeeds of suppressing competition, reducing consumer welfare, raising costs, impeding speech and more. Antitrust gets away with this because it operates on the perverse principle that, as Fred L. Smith Jr. put it long ago, “no business is entitled to its property if that property can be redeployed so as to expand output,” and that business has “no right in principle to dispose of its property as it sees fit, but only a conditional freedom so long as it helps maximize some social utility function.”

Antitrust regulation is contradictory. No company, nor conceivable combination of them, ever possesses more power than the handful of government enforcers lording over every firm in the entire economy. And antitrust’s premises are wrong: Coercive monopoly power is not a market phenomenon at all. It is too often ignored that much early industrial dominance was deliberately imposed by regulation or government favor, such as the granting of exclusive franchises that outlawed competition, created monopolies and sustained them for decades at the expense of competition and new platform wealth creation. Neither the tech nor the country will benefit from distortionary intervention. Rivals’ competitive responses to a “monopolist” and the potential for them to upend entire industries are ever present.

In this respect, antitrust enforcement cannot maximize social utility even on its own myopic terms. Markets interactions are dynamic, not static, and the antitrust committee’s report will be outdated soon enough. Enforcement actions taken to be beneficial in reality deny consumers the competitive responses to the purported bad behavior or harmful commercial activity, and make society and consumers poorer. It bears repeating that businesses do not operate in a vacuum; they face an assortment of upstream, downstream, and lateral stakeholders and watchdogs that regulate them including suppliers, business customers, the media, capital markets, competitors and advertisers. Antitrust undercuts these complex interactions and replaces them with a sledgehammer ruling; or an axe.

The big is bad notion being resurrected today needs to be ditched fast. For over a century now, the largest companies could have, perhaps, been even larger—checking one another and adding jobs. GDP and societal wealth could be far greater than it is, minus the antitrust threat. In turn it is straightforward to imagine companies vastly larger than even those of today, particularly as entrepreneurs expand global operations in new sectors like artificial intelligence, autonomous vehicles, smart cities, commercial space activities and more. Antitrust now punishes tomorrow’s consumer beneficiaries of these resource-intensive innovations to the extent they are pre-empted by forced “smallness.”

A problem alongside antitrust is the administrative state’s funneling of wealth-creating sectors into artificially segregated regulatory regimes (such as at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the Federal Communications Commission, the Federal Aviation Administration, and the Department of Energy). This artificial governmental siloing disrupts potential synergies and makes network sectors — and “platforms” in today’s parlance — smaller and less integrated than they could otherwise be. Drone recharging stations, for example, could be deployed alongside 5G cells in negotiations with landowners. Already dampened by the administrative state siloing, subjecting large-scale commercial endeavors to the antitrust regulatory threat hobbles them still further.

The point isn’t to downplay economic power but to assert that a powerful economic entity can be offset and disciplined by others, and antitrust stands in the way of that iterative process. Every merger already endures Mother-May-I filing delay rather than immediate execution. Perhaps more efficient partial mergers or “collusions” rather than inefficient total mergers could occur without antitrust influence. Mergers that do take place can be sometimes suboptimal since prior transactions involving one or all parties that would have made the present one moot were previously denied, rendering the current transaction a second-best “market” move compared to what could have occurred. Better for normal discipline by competitive process to rule.

A corporation is often deemed an artificial person. Even the largest of firms is characterized by a series of intangible relationships, and is in that respect a “fiction.” Yuval Noah Harari, in “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind,” using Peugeot as an example, put it this way: “All the managers could be dismissed and its shares sold, but the company itself would remain intact….Peugeot SA seems to have no essential connection to the physical world. Does it really exist?” He continues, “Peugeot is a figment of our collective imagination. Lawyers call this a ‘legal fiction.’”

Fiction can govern fiction better than the heavy, disruptive hand of Washington that seems all too real to the ones in the crosshairs. And it is all for naught. Professors Geoff Manne and Joshua Wright describe in an article called “Innovation and the Limits of Antitrust” the high social costs that accompany interference with poorly understood innovations and business practices.

The illusory protection of competition via antitrust, sometimes motivated by score settling and the pursuit of fame, is a category of regulation with too many beneficiaries, including an antitrust bar, to easily eliminate. But it could make a great topic for the House Judiciary Committee’s next 400-page report.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle The latest drone news

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle The latest drone news