BY CARLOS ANTARAMIÁN

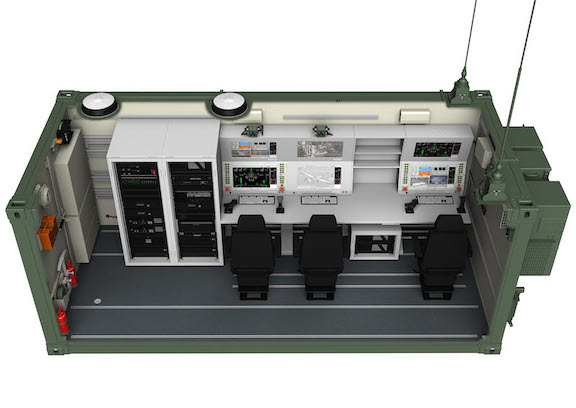

Bayraktar, a Turkish word meaning “standard bearer,” is an unmanned aerial combat vehicle (UAV), a drone capable of carrying up to 150 kilograms of munitions or missiles and flying at an altitude of 23,000 feet at a velocity of 220 km/h continuously for 24 hours. The development of this drone is attributed to a graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Selçuk Bayraktar who, in addition to being co-CEO of the Bayrak company with his brother Haluk, is the son-in-law of Turkish president Recep Tayip Erdogan.

Despite the U.S. government-imposed prohibition on the sale of inputs for drone construction on Turkey (U.S. Arms Export Control laws), which reflects the concern that these unmanned vehicles could be used against the Kurdish population, Bayrak managed to triangulate purchases through companies outside the U.S., including a missile-loading system in 2015 from the British company EDO (property of L3Harris Technologies based in the U.S.) and the acquisition of other inputs from Germany (speed regulator system), Austria (Rotax motors), and Canada (optical and infrared cameras).1 Those operations allowed Bayrak to finally assemble its fearsome Frankenstein.

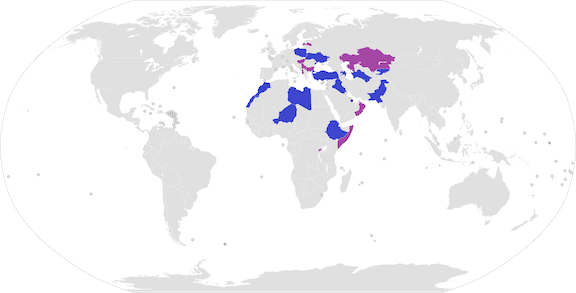

The success of Bayraktar TB2 in the military aggressions in which it has been used has brought the company new orders: after Qatar (2017), Ukraine (2019), Ethiopia (2019), Azerbaijan (June 2020), Tunisia (2020), Morocco (2021), and Turkmenistan (2021), Poland (2021) became the first NATO country to purchase these drones2, and currently there is interest in another dozen countries, including Lithuania and Great Britain. For a few decades, U.S. and Israeli companies dominated the UAV market, but today Ankara is an emerging power as the second-largest manufacturer of armed drones in the world, behind only the U.S. and in front of the select group of manufacturers of these weapons: Israel, China, Pakistan, and Iran.

The first “test field” for the Bayraktar drones was an operation called “Olive Branch” in the Rojava, the Kurdish region in northern Syria where it is believed that the Turkish army debuted its drone and where it killed its first victim on September 8, 2016, before going on to make 449 incursions and destroy, with great precision, land-based Kurdish positions, without exposing a single pilot to combat. This new technological capacity allowed Turkish planes and helicopters, now freed from attacks by the Kurdish defense systems, to make many more incursions against both military and civil positions.

The capacity that the Turkish army acquired to control and nullify the Kurdish armed forces and to terrorize the Kurdish population in northern Iraq thanks to these low-cost drones (each one costs around 5 million dollars) spurred great interest among the country’s military allies. The Ethiopian government has used them against Tigray rebels since January 2020, according to information from the Pax for Peace organization, and although it is assumed that drones permit tactical strikes on precise objectives and avoid the civilian casualties that result from attacks by jets and helicopters, reports indicate that in both Kurdistan and Ethiopia drones have been aimed at civil populations3.

The success demonstrated in military operations in Kurdistan, Ethiopia, Libya, and Syria encouraged the Azerbaijan government to purchase at least five Bayraktar drones in June 2020, just a few months before the war of September 2020. Analysts have affirmed that this UAV, together with Israel’s Hermes-900 and Harop munitions –also of Israeli manufacture– have been responsible for destroying many of the anti-missile defense systems that the Armenian armed forces once had at their disposal.

The difference in arms spending between Armenia and Azerbaijan speaks eloquently: while Armenia invested some $634 million in 2020, Azerbaijan virtually tripled that figure by 2.238 million. This asymmetry in weapons spending, both qualitative and quantitative, by Azerbaijan in 2020, changed the balance of power between the two nations. But more than this superiority in investment, analysts consider that it was the change in Turkey’s foreign relations policy in September 2020, added to Azerbaijan’s access to Turkish and Israeli drones, that shifted the balance of power significantly in favor of Baku and that led it to intensify the conflict and its efforts to recapture Karabakh. Despite the ceasefire signed on November 9, 2020, Bayraktar drones continue their incursions into the territory of Karabakh, as occurred on March 25 in Parukh when three Armenian soldiers were killed.

As occurred in Ethiopia, it is likely that during the 44-day War, Turkish operators commanded the Bayraktar units, since it is unlikely that Azerbaijan soldiers would have been able to acquire the ability to operate such complex drones between the purchase of the weapons (June 2020) and the onset of the war (September 27, 2020). The same suspicion exists in the case of the Ukraine, as Levent Kenez of the newspaper Nordic Monitor4 observed upon showing a video shared by the commander-in-chief of the Ukrainian army that showed an attack on supposed Russian positions in which the operators speak Turkish5. If that video is authentic, it would provide evidence to confirm Turkey’s direct participation in the conflict between Russia and the Ukraine. In turn, this would raise the question of whether Turkish soldiers (military drone operators) have also participated in the wars in Karabakh and the Ukraine. Both the sale of drones and the deployment of Turkish operators require the permission of the Turkish government and must be validated by the Ministry of Defense and the Foreign Ministry. Moreover, in a country like Turkey, decisions of this magnitude would depend, as well, on the maximum authority.

As part of the tightening of military relations with the Ukraine, Erdogan signed an accord during his visit to Kiev in February 2022 that committed Turkey to install a factory to produce Bayraktar drones in Ukrainian territory for 49 years, in addition to building an entertainment center. Before the onset of the conflict on February 24, Ukraine had around 20 TB2 drones, and there is proof that they were used in the Donbas region in October 20216 in an act condemned by the Kremlin, which stated that the delivery of the drones could destabilize the situation along the line of contact7. In early March of this year, despite efforts by President Erdogan to mediate the conflict, Turkey sent a new load of drones to the Ukraine. In September 2013, Turkey signed the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), an International Agreement conceived to regulate the conventional weapons trade, including armed drones. That Treaty has not yet been ratified. In September 2021, the government promised8 to complete the process, but ratification clearly continues in suspense.

Following the example of Azerbaijan, Morocco has also purchased the combination of Bayraktar TB2 drones (13 units at a cost of $70 million)9 and Israeli Harop munitions and has used these weapons against the Polisario Front and –it seems– also against civil Algerian drivers transporting cement in the Western Sahara in November 202110. A few weeks ago, the Spanish government turned its back on the Polisario Front independence movement in the Western Sahara in a move that has puzzled Algeria, which opposes Morocco’s expansionist policy in the zone. This conjuncture, and the presence of Bayraktar drones, may well cause an escalation of the conflict between these two African countries.

The trade in armed Turkish drones has drawn widespread attention in, and criticism by, the international community. In response to the denouncements by the Kremlin in October 2021, Turkey’s Foreign Relations Minister, Mevlüt Çavuçoglu, argued that although the drones were made in Turkey, once sold they belonged to Ukraine and could no longer be called Turkish weapons. Alper Coskun11 sustains that this kind of “washing one’s hands” in the arms trade contradicts the principle of responsible conduct implicit in the treaties that seek to control weapons exports and the international law that Turkey has signed, and also contradicts years of criticism that Turkey has leveled at other countries, including its allies, claiming that they have sold arms to Kurdistan Workers’ Party, a group that Turkey, the European Union, and the U.S. all consider a terrorist organization. Coskun holds that implementing a political strategy that gives transparency to sales of drones, especially if guided by respect for international law, should be a high-priority task for Ankara, as it would help erase the stigma of being a trafficker of destabilizing weapons. This is, however, unlikely, especially because so many countries are selling weapons and there is no international mark of reference that establishes global norms for the sale of armed drones. As a result, Turkey will continue to modify the balance of power in many Middle Eastern conflicts and, as a propaganda slogan broadcast on Turkish television after the 44-day War in Karabakh boasted: “Turkish drone power is heating up frozen conflicts.”12

Carlos Antaramián is an anthropologist based in Mexico and has written several articles related to Armenian communities in Latin America.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle The latest drone news

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle The latest drone news